Forever Faithful

The Story of Shep

Fort Benton

By Cathy Moser

Photography Contributed

Along the walking trail on the levee fronting the Missouri River in Fort Benton, several bronze statues memorialize characters who brazed a legacy in Montana by foot, hoof, or paw. One of the sculptures is of a Fort Benton sheepdog whose life was a faithful testament to the bond between dog and human.

The dog and his sheepherder came to Fort Benton in August 1936 when the sheepherder checked himself into the hospital. The brown and white dog, possibly part collie, waited outside, sniffing everyone who strode in and out of the facility. But with each passing person, no one smelled like the sheepherder, and the dog’s tail quit wagging.

The sheepherder died three days later. A procession conveying his body from the hospital to the mortuary to the train station was followed closely by the dog. At the train station, a swarm of passengers scrambled to board while others jumped to the platform. Railroad men rushed to load trunks, crates, and suitcases. The sheepherder’s casket was hoisted into a car and the forlorn dog watched as the train chugged away and disappeared.

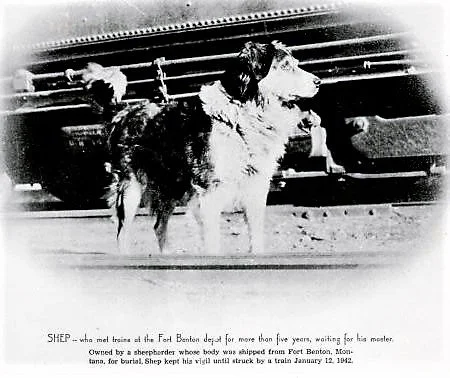

Later that day, a shrill whistle blew when the next train rolled into Fort Benton. The sheepdog anxiously appeared to greet it… and the next train… and the next. No matter the hour, and whether it be rain, snow, or oppressive heat, the dog faithfully met every train and sniffed every passenger. After each inspection, his tail stopped wagging and drooped as he turned away.

The men manning the Great Northern train yard assumed the dispirited dog would eventually wander away, but he never did. Instead, he dug a bed beneath the station platform and beat a mile-long path to the Missouri River where he drank. Station agents quit shooing him away and sympathetic stewards staffing the dining car started tossing him food scraps. The crew named their new companion Shep.

By 1939, Ed Shields, a Great Northern conductor, had pieced together bits of Shep’s history. No one could recall the sheepherder’s name, only that he died, and his body was sent East for burial. Shields’ interest in Shep inspired articles which he wrote for the local newspaper, The River Press. Railroad magazines and newspapers worldwide soon picked up and published Shields’ articles. The stories about Shep’s unflagging devotion brought hope and pleasure to Americans weary of the Great Depression.

Fan mail swamped the Great Northern railroad office, and a secretary was assigned specifically to handle it. The nation’s train travelers hoping to see Shep requested they be routed through Fort Benton. Thousands of passengers peered at Shep through train windows. Multitudes snapped his picture as he stood on the station platform. Children tried to entice him to play, but the many friendly gestures only overwhelmed Shep and he retreated to the security of his dirt bed underneath the platform.

The famed Montana painter, Olaf C. Seltzer, depicted the dog’s vigil on canvas. American cartoonist Robert L. Ripley, famed for his “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” syndicated cartoons and columns, featured Shep’s steadfast loyalty. America’s dog lovers sent contributions for his care, only to be returned by the railroad men. At least 50 sheepherders begged to have him, and some even traveled to Fort Benton to make their request in person. But Shep was a shy, distant dog who disliked attention, so the railroad men gently declined all offers to adopt him. It was clear he was a one-man dog.

Over the years, Shep’s hearing and sight diminished. Stiffening joints slowed his once brisk trot to a painful stroll. A dusting of snow covered the train yard on the morning of January 12, 1942 as the Great Northern No. 235 chugged into the station. When Shep tried to leap off the snow-dusted rails to greet the passengers, he slipped and fell under the train wheels where he died instantly.

In 1992, fifty years after Shep’s death, the Fort Benton community launched fundraising efforts to erect a monument on the levee. That goal was reached on June 26, 1994, and renowned sculptor, Bob Scriver, was contracted to create a large bronze of Shep.

News of his death traveled over the Associated Press wires. The Great Northern workers mourned their loss. On the afternoon of January 14, the Fort Benton Boy Scouts carried a small wooden casket to the top of a bluff overlooking the train yard. Hundreds of mourners trailed the boys, including the Fort Benton mayor and Ed Shields, then-Mayor of Great Falls. Local minister Ralph Underwood delivered a eulogy praising Shep’s devotion, and the scouts carefully lowered the casket as a bugler played Taps. A concrete monument was later erected at the gravesite and still stands today.

Ed Shields didn’t forget Shep’s vigil. A few years after the dog’s death, he turned his articles into a booklet the Great Northern sold to its passengers for a quarter. Shields also established the “Shep Fund,” with the proceeds benefiting the Montana School for the Deaf and Blind in Great Falls. The school received more than $50,000 in donations.

In 1992, fifty years after Shep’s death, the Fort Benton community launched fundraising efforts to erect a monument on the levee. That goal was reached on June 26, 1994, and renowned sculptor, Bob Scriver, was contracted to create a large bronze of Shep. Hundreds of people gathered to dedicate the Shep Memorial. The homage inscribed in the pedestal states, “Forever Faithful.”